Subsidiarity and the Sovereign Village

What We Learned at Zuitzerland About Building Network Societies

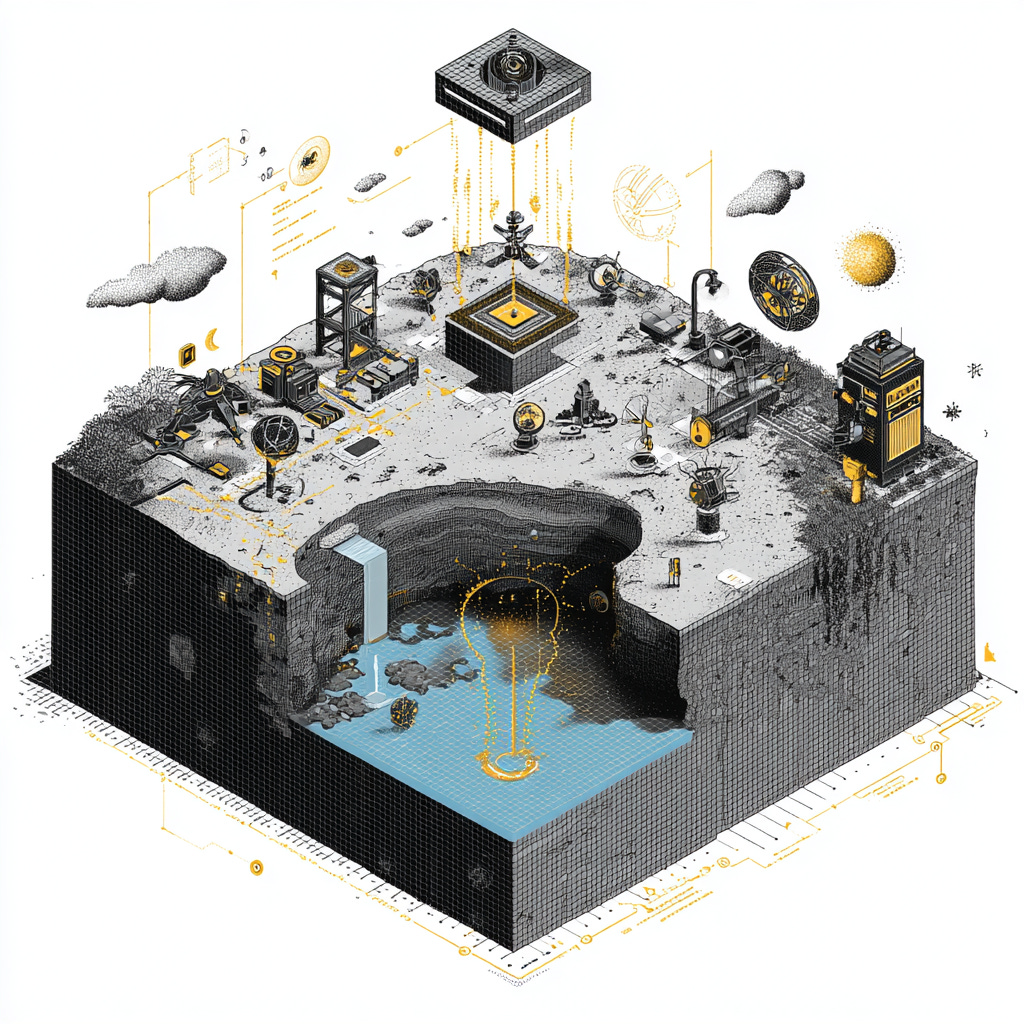

In technology, a "sandbox" refers to an isolated environment where experiments can be conducted safely, innovations can be tested, and failures can occur without threatening the integrity of the larger system. While crucial to software development, this concept can just as easily be applied to the experimentation of societies themselves.

Throughout history, Switzerland has served as a kind of governance sandbox: a controlled, semi-insulated space where new political forms were tested, refined, and sometimes exported far beyond its mountainous borders. The secret sauce behind Switzerland’s renowned reputation as a model of civic engagement and political stability is the concept of subsidiarity. But we’ll get to that below.

This spring, the Polis Labs team joined Zuitzerland (part of the broader Zuzalu archipelago) for a month-long exploration of its "future society sandbox." Based at a stunningly beautiful location in the Swiss Alps, the Zuitzerland pop-up village served as a playground for experiments in decentralized governance, regenerative economics, and new societal models.

One of our hypotheses at Polis Labs is that human flourishing comes not from perfecting top-down control, but from building bottom-up trust. By taking both an observational and direct, participatory approach at Zuitzerland, we gained valuable insights into how the Swiss concept of subsidiarity works when real people, with real needs, consider what it would take to build a governance system from scratch.

Switzerland: A 700-Year Governance Laboratory

As we dive deeper into the study of network states, parallel societies, and emerging social models, it is important to understand the historical context of Switzerland's long-standing legacy of political innovation, particularly at the subnational level.

Many people may not be aware of how deeply Switzerland embodies the principle of subsidiarity, which is the idea that decisions should be made at the lowest capable level of governance:

Under the notion of autonomy, within the framework of laws and constitution, lower units organize themselves and decide how to accomplish their tasks. Higher levels should thus only take over powers of the lower levels when the lower levels are not able to assume their responsibilities or when an overarching solution is absolutely needed.

— Andreas Ladner, Switzerland: Subsidiarity, Power-Sharing, and Direct Democracy

In practice, this means that the 2,000+ municipalities in Switzerland, spread across 26 cantons, all handle a wide range of local issues, escalating only what is necessary to cantonal or federal levels. This system has allowed Switzerland to function not as a monolith but as a federation of semi-sovereign communities, much like the ideal many network societies today aim to achieve.

This did not occur easily, though. The modern Swiss state emerged from centuries of conflict, negotiation, comprise, and experimentation. Beginning with the 1291 Federal Charter, small cantons formed alliances based on the need for mutual defense and self-governance. This decentralized federation concept was revolutionary, given the total dominance of absolute monarchies in Europe at the time. But it wasn’t always stable. Religious wars, economic rivalries, and political fragmentation led to frequent upheaval until the post-Sonderbund War reforms in 1848 finally codified a federal constitution. That constitution formalized the subsidiarity principle, shaping what has arguably become one of the world’s most successful multi-level governance systems.

Swiss Experimental Governance in Action: From Geneva to Appenzell

Some early iterations of Swiss governance sandboxes include Geneva’s fusion of civic and religious authority under Calvin, built on a values-driven civic system, and Appenzell’s Landsgemeinde, an open-air vote that embodied direct democracy and hyper-local sovereignty.

Even more striking is how Graubünden’s pluralistic League of the Three Leagues united multiple linguistic communities under a decentralized, yet functional system: a direct historical precursor to the idea that cultural heterogeneity can thrive within federated political frameworks. This last one is a foundational principle of the network state concept, which aims to bring together like-minded individuals from all over the globe.

Zuzalu: A Subsidiarity Prototype for the 21st Century

Fast-forward to the present: in 2023, Ethereum co-founder Vitalik Buterin helped launch Zuzalu, a pop-up city of around 200 people in Montenegro. Designed to last two months, Zuzalu aimed to embody the logic of subsidiarity in real-time. Local pods made decisions, rituals formed organically, and governance emerged from the bottom up. The idea was that participants weren’t just cohabiting, they were co-creating society. While we cannot say whether Vitalik had Switzerland in mind originally with Zuzalu, the Montenegro approach to conflict resolution, infrastructure sharing, and social governance reflected a subsidiarity-first approach.

Zuitzerland: Scaling the Sandbox

In 2025, Vitalik and his collaborators took the next step with Zuitzerland, hosted in Switzerland itself. This was both an intentional homage to the nation that pioneered the principles being tested and an experiment with the possibility of building a permanent hub in the country. Drawing on Switzerland’s federalist DNA, Zuitzerland became a larger, more intricate experiment in community building.

Combining the lessons of Switzerland’s historical sandbox with the real-time experiments of Zuzalu and Zuitzerland, our team had the following takeaways:

Delegate Downward First: Just as in Switzerland, decisions in a network society should ideally start at the community level. Give real authority to clusters of 100–300 people to manage shared resources, set local norms, and resolve disputes. Only escalate when coordination requires it.

Consider Governance Diversity: Different subcommunities may wish to explore different social contracts, e.g., consensus in one, quadratic voting in another, and reputation-based systems elsewhere. Like the Swiss cantons, allowing for pluralism under a shared constitutional shell could be the way forward.

Facilitate Norm Formation: Forming shared community norms serves two purposes. First, shared norms build shared meaning, the glue of subsidiarity. Second, a community charter co-created from the bottom up and based on community norms can be used as the foundation for a conflict resolution system based on community consent and not through enforcing rules imposed from top-down authority.

Modular Infrastructure, Shared Protocols: Invest in core tools that enable autonomy: interoperable ID systems, dispute resolution pathways, digital voting protocols, and transparent budgeting tools. Think of these as your equivalent to Switzerland’s excellent public transit system, serving to connect, but not override.

Human Flourishing Through Layered Autonomy

At Polis Labs, we believe the future belongs to interoperable civilizations, i.e., to federations of communities that are sovereign in character but unified in principle. Subsidiarity offers not just a method of governance but a philosophy of freedom, responsibility, and dignity.

The common thread between Swiss subsidiarity and Zuitzerland’s governance experiments is trust: trust that local communities can govern themselves, and trust that resilience emerges from decentralization, not from uniformity.

It is also important to note that the Zuzalu and Zuitzerland experiments are not utopias. They are scaffolds. But they point to what’s possible: a world where governance is closer to life, where politics is reclaimed by the people most affected by its outcomes, and where network states don’t repeat the mistakes of centralized modernity.

As we continue researching and advising new societies, from eco-villages to blockchain cities, we encourage all founders and builders to ask: Are you designing for control, or for trust?

If it’s the latter, subsidiarity might just be your most powerful tool.

To further support our work at Polis Labs, consider donating to fund our next deep governance research project at Edge City, Patagonia. Donate via our Manifund crowdfunding campaign below.